You could be out in the middle of nowhere and as the days warm up the bush flies come out to annoy you. So where do they come from, why do they pick on me and how long do they live?

Bush flies are first noticeable in October. The numbers rise steeply in November and peak in December.

After the peak, the numbers fall off fast. By the end of January, almost all the bush flies are gone. (This sharp peak and sharp drop-off only happens in the south-west of Australia. In the south-east, the bush flies linger until March.)

What do they eat?

Blood, sweat and tears. (They’ll take blood from wounds — they don’t bite to draw blood.) It’s the protein they are after. They taste with their feet! That’s why they walk all over something before they eat. They also feed on dung, but the females can’t get enough protein from dung to develop their eggs.

This explains why bush flies are such a pest at barbeques. They want the blood and other protein-rich juices in the meat. But at barbeques, they are only looking for something to eat, not for a place to lay eggs. They never lay eggs in meat or in wounds.

And they’re not usually attracted to sugary things like cakes. But they’ll nibble at them if there’s nothing else going.

Their minimum survival needs are for moisture and carbohydrates. These they could get from plants alone. But with this diet, the females wouldn’t get protein to develop their eggs and bush flies would die out.

How long do they live?

In hot weather, they live about a week. In cool weather, two to four weeks. Without water, they only live about a day.

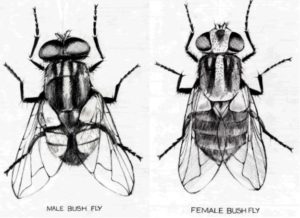

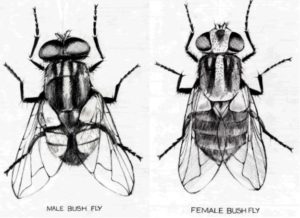

How can you tell males from females?

Look at their eyes. The male’s eyes are close together, almost touching. The female’s eyes are much farther apart.

There are also other ways. The wings of a resting female are almost parallel to her body. In a male, the wings stand out at an angle.

The female’s body is mottled grey all over. In the male, the middle segments of his abdomen are creamy-white or yellow (except a black hourglass pattern on the mid-dorsal line).

Where do bush flies sleep?

Bush flies sleep on vegetation. They keep off the ground. They like to roost on the tips of leaves and twigs. For example, you can often find them roosting on the tips of Spinifex grass.

Source: The fly in your eye

http://www.viacorp.com/flybook/fulltext.html#baghat